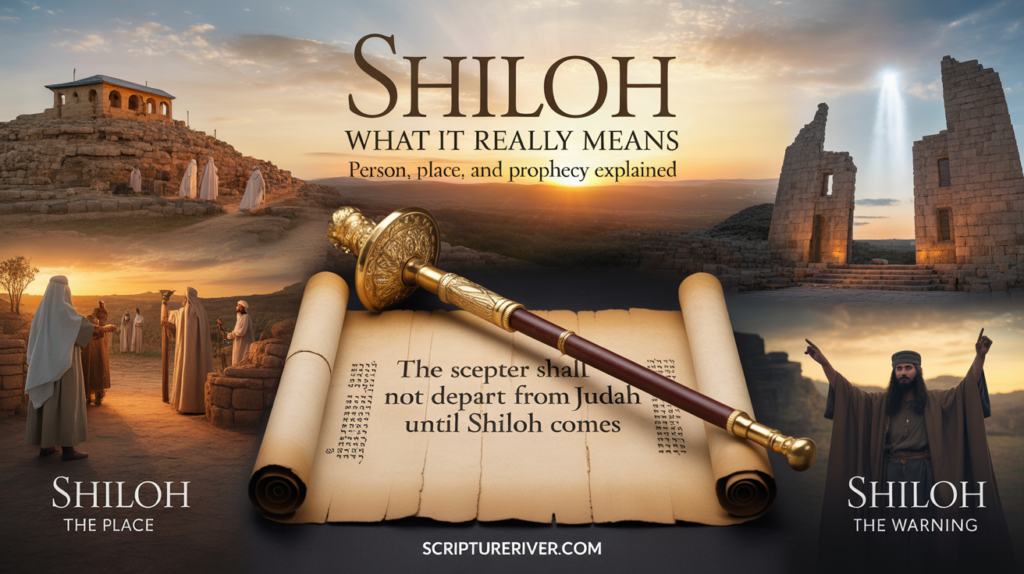

Shiloh appears 33 times in the Old Testament, yet most Christians couldn’t tell you what it is or why it matters.

Is it a person? A place? A prophetic title?

The answer is yes to all three, depending on which biblical passage you’re reading.

This creates confusion that prevents people from understanding some of Scripture’s most important prophecies and historical events.

When Jacob blessed his son Judah in Genesis 49:10, he used the word “Shiloh” in a messianic prophecy that Jews and Christians have debated for thousands of years.

When the Israelites set up the tabernacle after conquering Canaan, they chose Shiloh as its location for over 300 years.

When Jeremiah warned Jerusalem about coming destruction, he pointed to Shiloh as an example of what happens when God’s people persistently reject Him.

Understanding Shiloh in its three biblical contexts unlocks crucial insights about God’s promises, Israel’s history, and prophecies about the Messiah.

Let’s examine what Scripture actually teaches about Shiloh and why it still matters today.

Shiloh as a Place: Israel’s First Worship Center

The most frequent biblical use of “Shiloh” refers to a specific city in ancient Israel located in the tribal territory of Ephraim, approximately 20 miles north of Jerusalem in the central hill country.

Joshua 18:1, English Standard Version (ESV)

“Then the whole congregation of the people of Israel assembled at Shiloh and set up the tent of meeting there. The land lay subdued before them.”

The Tabernacle’s Home for 369 Years

After Israel conquered Canaan under Joshua’s leadership, they chose Shiloh as the location for the tabernacle, the portable worship tent that housed the Ark of the Covenant.

According to biblical chronology, the tabernacle remained at Shiloh from approximately 1400 BC until its destruction around 1050 BC.

Archaeological excavations at Tel Shiloh, conducted by Israel Finkelstein and documented in his work on early Israel, have uncovered remains consistent with a major religious center during this period, including large storage facilities and evidence of extensive food preparation suggesting sacrificial meals.

Why Shiloh Was Chosen

Scripture doesn’t explicitly state why the Israelites selected Shiloh for the tabernacle’s location.

Biblical geographer Yohanan Aharoni suggests in his work on biblical geography that Shiloh’s central location made it accessible to all twelve tribes, while its position in Ephraimite territory honored Joseph’s descendants without favoring Judah, whose future kingship would create tribal tensions.

Hannah’s Prayer at Shiloh

One of Scripture’s most significant events at Shiloh was Hannah’s desperate prayer for a son, recorded in 1 Samuel 1.

She vowed that if God gave her a child, she would dedicate him to the Lord’s service at the tabernacle.

1 Samuel 1:10-11, Christian Standard Bible (CSB)

“Deeply hurt, Hannah prayed to the Lord and wept with many tears. Making a vow, she pleaded, ‘Lord of Armies, if you will take notice of your servant’s affliction, remember and not forget me, and give your servant a son, I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life.'”

God answered Hannah’s prayer with Samuel, who grew up serving at Shiloh under the priest Eli and became one of Israel’s greatest prophets.

Shiloh’s Destruction

Shiloh’s significance ended catastrophically when the Philistines destroyed it around 1050 BC after capturing the Ark of the Covenant in battle.

Psalm 78:60 records God’s response: “He abandoned the tabernacle at Shiloh, the tent where he dwelt among men.”

Jeremiah 7:12-14 later references Shiloh’s destruction as a warning to Jerusalem: God didn’t spare Shiloh despite it housing His tabernacle, and He wouldn’t spare Jerusalem despite Solomon’s temple if the people persisted in sin.

Shiloh as a Messianic Prophecy: Genesis 49:10

The most debated use of “Shiloh” appears in Jacob’s deathbed prophecy about his son Judah.

Genesis 49:10, King James Version (KJV)

“The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the gathering of the people be.”

The Translation Controversy

Modern translations handle this verse differently because the Hebrew text is grammatically complex.

Compare these translations:

New International Version: “until he to whom it belongs shall come”

English Standard Version: “until tribute comes to him”

Christian Standard Bible: “until he whose right it is comes”

The Hebrew phrase “ad ki-yavo Shiloh” can be translated multiple ways depending on how you parse the words.

Is “Shiloh” a proper name, or does it mean “to whom it belongs”?

Ancient Jewish Interpretation

The ancient Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, called the Targum Onkelos, translates this phrase messianically: “until the Messiah comes, to whom the kingdom belongs.”

Early Jewish interpreters understood Jacob to be prophesying about a future ruler from Judah’s line.

The Talmud (Sanhedrin 98b) lists this verse among messianic prophecies, though later rabbinic interpretation became more cautious as Christians used it to argue for Jesus as Messiah.

Christian Interpretation

Christian theologians from the early church fathers through modern scholars have traditionally understood this as a messianic prophecy.

The “scepter” represents royal authority that would remain in Judah’s tribe until the ultimate king, the Messiah, arrived.

According to Old Testament scholar Victor Hamilton in his Genesis commentary, Jacob was prophesying that Judah’s descendants would produce Israel’s kings, culminating in the Messiah who would gather all peoples to Himself.

Historical Fulfillment

Judah’s tribe did produce Israel’s royal line.

King David came from Judah around 1000 BC. Solomon and subsequent kings of the southern kingdom descended from David’s line through Judah.

Even after the Babylonian exile, Jewish genealogical records tracked Davidic descent through Judah.

Jesus was born into this royal lineage.

Both Matthew 1 and Luke 3 trace Jesus’s genealogy through Judah and David, fulfilling Jacob’s prophecy about the scepter remaining in Judah until the ultimate ruler came.

Shiloh as a Warning: Jeremiah’s Message

Jeremiah used Shiloh’s destruction as an object lesson for Jerusalem in the 6th century BC.

Jeremiah 7:12-14, New International Version (NIV)

“Go now to the place in Shiloh where I first made a dwelling for my Name, and see what I did to it because of the wickedness of my people Israel. While you were doing all these things, declares the Lord, I spoke to you again and again, but you did not listen; I called you, but you did not answer. Therefore, what I did to Shiloh I will now do to the house that bears my Name, the temple you trust in, the place I gave to you and your ancestors.”

The Context of Jeremiah’s Warning

Judah’s people believed Jerusalem was invincible because God’s temple was there.

They thought God would never allow His dwelling place to be destroyed, regardless of their behavior.

Jeremiah shattered that false security by reminding them of Shiloh.

God had allowed Shiloh, which housed the tabernacle and His presence, to be completely destroyed when Israel’s sin became intolerable.

The same would happen to Jerusalem and the temple.

Fulfillment of Jeremiah’s Warning

Jeremiah’s prophecy came true in 586 BC when Babylon destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon’s temple.

The city that thought itself secure because of God’s presence was devastated just as Shiloh had been centuries earlier.

This demonstrates a consistent biblical principle: God’s presence doesn’t protect places or people who persistently reject Him.

Even locations He specifically chose for His name can be destroyed when the people there abandon Him.

Archaeological Evidence at Tel Shiloh

Modern archaeology provides physical evidence supporting the biblical account of Shiloh.

Danish archaeologist H. Kjaer first excavated Tel Shiloh in the 1920s and 1930s.

More extensive excavations by Israel Finkelstein in the 1980s uncovered substantial remains from the period when biblical Shiloh functioned as Israel’s worship center.

Findings include:

Large storage jars suggesting extensive food storage consistent with a worship center handling sacrifices and festival meals.

Destruction layer from approximately 1050 BC matching the biblical timeline for Philistine destruction.

Evidence of abandonment after the destruction, with the site remaining largely uninhabited for centuries afterward, exactly as biblical texts describe.

Ritual objects including pottery and installations consistent with cultic activity.

While archaeology cannot prove that the tabernacle specifically stood at Shiloh, the physical evidence aligns remarkably well with the biblical narrative of a major worship center that was violently destroyed and abandoned.

What Shiloh Teaches About God’s Character

Understanding Shiloh’s three biblical contexts reveals important theological truths.

God Keeps His Promises

Jacob’s prophecy about Shiloh (if understood messianically) was fulfilled in Jesus from Judah’s line.

God’s promise that the scepter would remain in Judah until the ultimate ruler came proved true across a thousand years of history.

God’s Presence Doesn’t Guarantee Protection

Shiloh housed the tabernacle and God’s presence, yet God allowed its destruction.

Jerusalem housed the temple and God’s presence, yet God allowed its destruction. Physical proximity to God’s dwelling place doesn’t protect people who reject Him.

God Uses History to Warn

Jeremiah pointed to Shiloh’s destruction as evidence that God would judge Jerusalem if they didn’t repent.

Past judgments serve as warnings about future consequences if people persist in sin.

God Values Obedience Over Location

What happened at Shiloh mattered more than that it was Shiloh. Hannah’s faithful prayer pleased God. Eli’s sons’ corruption grieved God. Samuel’s service honored God. The location itself held no magical protective power apart from the people’s faithfulness there.

Frequently Asked Questions About Shiloh

Does Shiloh in Genesis 49:10 refer to Jesus?

Christian interpretation has traditionally understood this as a messianic prophecy fulfilled in Jesus, who came from Judah’s royal line.

Jewish interpretation varies, with some ancient sources viewing it messianically and later sources offering alternative translations that don’t specifically reference the Messiah.

The Hebrew text allows both interpretations, depending on how you translate the phrase.

Can you visit Shiloh today?

Yes. Tel Shiloh is an archaeological site in the modern West Bank, located near the Palestinian town of Turmus Ayya.

The Israeli archaeological park at the site includes remains from ancient Shiloh and a museum explaining the site’s biblical significance. Security situations in the region can affect access.

Why did God allow Shiloh to be destroyed?

1 Samuel 2-4 records that Eli’s sons, who served as priests at Shiloh, were corrupt and treated God’s sacrifices with contempt.

Psalm 78:60 states God abandoned Shiloh because of Israel’s persistent sin and idolatry.

Shiloh’s destruction demonstrated that God’s patience with sin has limits, even at locations He chose for His presence.

What’s the difference between Shiloh and Jerusalem as worship centers?

Shiloh housed the tabernacle, a temporary tent structure. Jerusalem eventually housed Solomon’s temple, a permanent stone building.

Shiloh served as the worship center for about 369 years during the period and reign of the judges.

Jerusalem became the permanent capital and worship center under David and Solomon around 1000 BC and remained central to Jewish worship (despite temple destructions and rebuilds) through today.

Is there any modern significance to Shiloh?

For archaeologists and biblical historians, Shiloh provides physical evidence supporting biblical narratives about early Israelite worship.

For Christians, Shiloh serves as a reminder that God values obedience over religious locations and that His presence doesn’t protect people who persistently reject Him.

For Messianic prophecy interpretation, Genesis 49:10 remains significant in discussions about Old Testament predictions of Christ.

Cited Works

Aharoni, Y. (1979). The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Westminster John Knox Press. [Book]

Finkelstein, I. (1988). The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement. Israel Exploration Society. [Book]

Hamilton, V. P. (1995). The Book of Genesis: Chapters 18-50. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Book]

Keil, C. F., & Delitzsch, F. (1996). Commentary on the Old Testament: Volume 1, The Pentateuch. Hendrickson Publishers. [Book]

Peterson, E. H. (2005). The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. NavPress. [Bible Translation]

Strong, J. (2010). Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Hendrickson Publishers. [Reference Book]

The Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin. (1935). (I. Epstein, Ed.). Soncino Press. [Religious Text]

Wenham, G. J. (1994). Genesis 16-50. Thomas Nelson Publishers. [Book]